SINOHYDRO LINKED TO MAFIA THAT PAID FOR LAMIA AIRLINES’ PLANES

August 2011. President Morales in Beijing during the launch ceremony of the Tupac Katari satellite, manufactured in China for Bolivia. | Photo Xinhua

© Wilson García Mérida | Newsroom Sol de Pando in Brasilia

© Translation by Scott Campbell © Original in spanishWho would have thought that Bolivia’s main calamity in the 21st century, the prevalence of endemic corruption steamrolling the Plurinational State, took shape in Africa after crossing over from China…

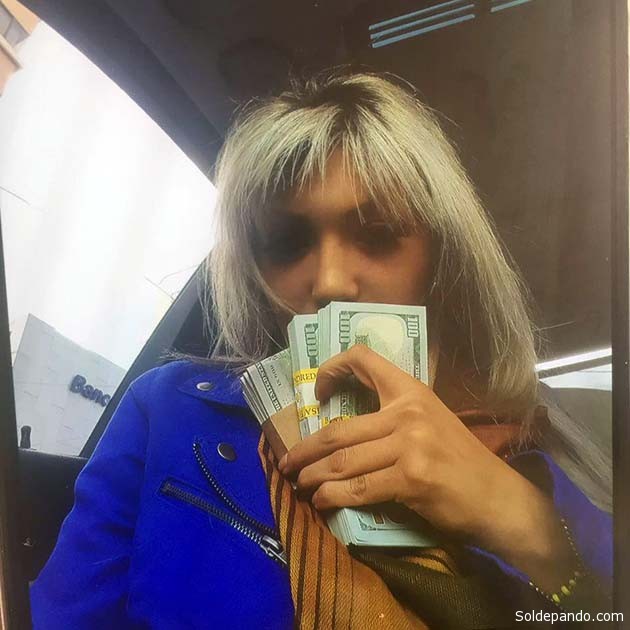

“My last partner was Mr. Shen Wei”, Gabriela Zapata told the court investigating her early enrichment in May 2017. “I didn’t know it was a crime to receive gifts from some of the partners I’ve had”, she said in justifying her income that exceeded $20,000 USD monthly from multiple sources.

Gabriela Zapata, the lover shared between president Evo Morales and his minister Juan Ramón Quintana. | Photo archive of Sol de Pando

The strange thing is that in 2010, even before meeting Wei or having a degree, Zapata acted as a representative in Bolivia for another Chinese company, CITIC, that was trying to take control over lithium mining in the Salar de Uyuni. In a confession she later retracted, Zapata identified Juan Ramón Quintana, at the time the Minister of the Presidency, as serving as her connection with the Chinese.

CAMC is one part of a conglomerate of Chinese construction firms, such as Sinohydro, Gezoiba, Sinopec, etc., that operate through offshore holdings created by magnate Sam Pa in the tax haven of Hong Kong.

Shen Wei and his family became partners with Sam Pa in several mega-businesses based in Central Africa. Before arriving in Bolivia, Shen Wei oversaw CAMC contracts in Angola, Cameroon and Zimbabwe. His father, Wang Wei —an important figure in the Chinese Communist Party— was Chargé d’affaires at the Chinese Embassy in Luanda, working closely with Sam Pa to turn Angola’s state oil company (Sonangol) into a joint Chinese-African venture under the control of the family of Angolan autocrat José Eduardo dos Santos. His daughter, Isabel, is president-for-life of the Portuguese-African corporation and supported by her father’s Chinese business partners.

GALLERY | The Sam Pa's tentacles

What is CAMC?

Dos Santos, the autocrat who ruled from 1979 to 2017, was re-elected several times and during recent decades had Chinese funding for his campaigns. When he fell ill, he promoted Defense Minister João Lourenço as his successor, also a close friend of Sam Pa.

In 2012, Sam Pa, as official representative of China Sonangol, began negotiations to buy the shipyards of the nearly bankrupt Spanish shipbuilder Rodman. He obtained 60% of the shares of Galicia-based oil-tanker factory, valued at close to one hundred million euros. Through the purchase of the Galician shipyard, Sam Pa’s objective was to expand by sea the marketability of African oil in Europe.

Ricardo Albacete, from Venezuela, was Sam Pa’s emissary and front man during the negotiations with Rodman shipyards in the Galician city of Vigo. Along with taking part in the purchase of the shipbuilder, he was responsible for managing Sam Pa’s investments in the aviation sector. During that time, Albacete received funds from Sam Pa to buy three airplanes with which Albacete created Lamia, a domestic airline based in Mérida, Venezuela.

According to an article published by the online outlet El Confidencial on November 30, 2016, the prestige that Sam Pa earned in Galicia thanks to his rescue of the Rodman shipyards, “placed Albacete in a privileged position, as word spread among Galician business people that Sam Pa had the intention of making more investments in Galicia and, therefore, everyone wanted to meet with his delegate in Spain. All this year and last, the Venezuelan spent months interviewing Galician entrepreneurs seeking capital for their businesses and political leaders. Regarding the latter, he even closed meetings to put them in contact with the Chinese magnate”.

At the end of 2014, negotiations to buy Rodman shipyards failed and Lamia was broke, unable to even buy fuel for its small fleet of Avro planes. The Chinese magnate had disappeared from the scene. Under a travel ban, he was being tried in Beijing by the Chinese Communist Party. In 2015, he was sentenced to prison for several acts of corporate corruption. The U.S. State Department demanded the Chinese government take him out of circulation because he had illegally made million-dollar diamond mining deals with the bloody dictatorship of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe. He was also being investigated by the DEA for money laundering.

Deprived of the money that Sam Pa provided him, Ricardo Albacete went into panic and bankruptcy. As La Voz de Galicia revealed, Sam Pa had offered to buy back Lamia’s airplanes —acquired in 2011 with his own money— to set up a new airline in Sierra Leone. While waiting for Bolivian approval for international flights in 2015, Albacete had his only operable plane parked in a hangar in Vigo’s Peinador airport, waiting for the Chinese godfather to arrive to close the deal with Rodman. But Albacete would never see Sam Pa again.

“The owner of Lamia prepared the Avro CP-2933 for transfer to Sam Pa, who was planning Sierra Leone’s first airline”, reported the Spanish newspaper that interviewed Albacete hours after the Chapecoense tragedy. “It was a verbal agreement, between friends, and we agreed that he would buy my four planes”, the devastated Venezuelan admitted to La Voz de Galicia.

Isolated from Chinese funding and discredited in Venezuela where he faces trial for fraud, Albacete took his planes to a military air base in Cochabamba, with the support of the then-Minister of the Presidency, who put him in contact with officers in the Bolivian Air Force (FAB). In this way, the Venezuelan found in Bolivia an opportunity to save Lamia by entering into shady agreements with the country’s most influential minister and Bolivian drug traffickers for future joint “operations”. As is known, Albacete “pressured” key authorities in Evo Morales’ government to grant Lamia a permit for international flights that forced the planes —designed only for short, domestic flights— to operate with a suicidal limit of fuel. On November 28, the trigger was pulled on this game of flying Russian roulette with a Brazilian soccer team aboard the Avro CP-2933 on the Santa Cruz – Medellín route.

Without fuel, the plane fell a few kilometers from the Colombian airport, killing 66 Brazilian passengers, almost all players from the Chapecoense soccer club, as well as its crew of four Bolivians and one Paraguayan. The tragedy, caused by the habitual lack of fuel in the plane’s overburdened tanks, had its origin —along with the fraudulent permit to fly out of Bolivian territory without meeting the technical and legal requirements— in the imprisonment of Sam Pa, Albacete’s financier, who left his loyal front man in total bankruptcy.

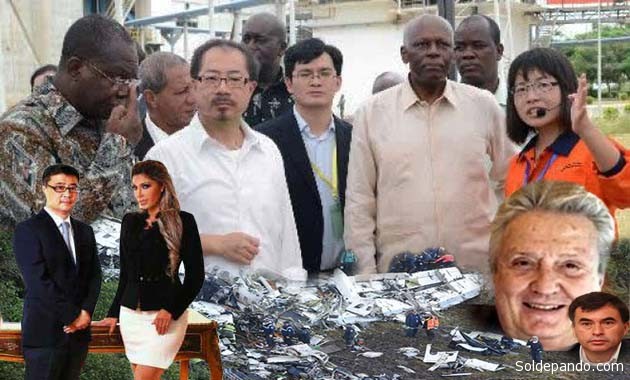

Sam Pa founded the empire of chinese construction companies in Africa, thanks to his relations with the angolan autocrat José Eduardo Dos Santos who privatized the state oil company Sinangol with chinese capital. Sam Pa is also a partner of Shen Wei, lover of the bolivian woman Gabriela Zapata, and financed the three planes of Lamia, an airline created by his venezuelan figurehead Ricardo Albacete. | Photomontage of Sol de Pando

Sam Pa and Sinohydro: The African “Car Wash”

Chinese workers in the streets of Luanda, 2011. In the background, the everlasting image of the stalinist autocrat of Angola José Eduardo dos Santos | Photo courtesy of Louise de Redvers for Sol de Pando

The presidential elections held in Gabon on the last Sunday of August 2016 —a former French colony where tribal power relations predominate— resulted in a scandal surprisingly similar to the Car Wash («Lava Jato» in portuguese) operation in Brazil. Except that the company systematically bribing corrupt candidates with million dollar “tips” was not called Odebrecht, but rather Sinohydro.

That case, dubbed “Sinohydro-gate” by the French media, is cited in a dossier prepared by Brazilian academic researchers in collaboration with the Brazilian Federal Police. That dossier, to which Sol de Pando had access as a contributor to the investigative group, looks at parallels between the strategies developed by Brazilian and Chinese companies to corrupt political systems with sophisticated methods of bribery using corporate expansion into the lucrative public works projects on a continental level.

During the last elections in Gabon, Jean Ping, the former Chancellor and son-in-law of the late autocrat Omar Bongo, was the favored presidential candidate to replace his brother-in-law, President Ali Bongo (heir to the Bongo dynasty). However, Bongo ended up being re-elected thanks to a scandal that embroiled his own relatives. Despite his charisma and prestige as the “anti-establishment leftist” inside the dynastic family, Jean Ping lost the elections to his brother-in-law following revelations that he had received bribes from the Chinese construction company Sinohydro.

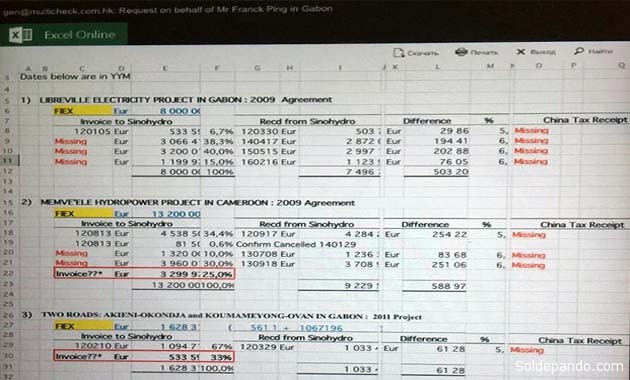

According to an investigation published on June 23, 2016, by the French newspaper Mediapart, Jean Ping’s wife, Pascaline Bongo (sister and former chief of staff for now re-elected President Ali Bongo, also famous for being Bob Marley’s girlfriend one year before the Jamaican singer’s death in 1981) and their son, Frank Ping, had received juicy “commissions” from Sinohydro since 2008. These were in exchange for important contracts for the construction of a giant hydroelectric power plant on the Ogooué River as well as four major highways: Leyou-Lastourville, Akieni-Okondja, Koumameyong-Ovan and Mikouyi-Leroy Crossing. These works were financed by Chinese credit from Eximbank (the Export-Import Bank of China). Crooked deals led to similar projects in Cameroon.

Jean Ping primarily received bribes from Sinohydro between 2008 and 2012, when he held the presidency of the African Union Commission, based in Ethiopia. From there, he exercised influence over all the organization’s member states, promoting works contracts in favor of the Chinese construction company. Under Ping’s presidency, the Chinese government and Sinohydro donated funds to construct a modern building to serve as the African Union’s headquarters.

Pascaline Bongo and her son Frank Ping created at least three offshore companies that operated in a building on Queensway Avenue in Hong Kong owned by Chinese magnate Sam Pa (in charge of directing lines of credit from Eximbank to Africa). These were Ping Ping and Consulting Limited, the FIEX society, and the consultancy Osiris, to whose accounts Sinohydro paid bribes to the Ping family in the form of consulting “honorariums” and other non-existent services.

After the revelations in Mediapart’s report, Sinohydro executives together with Jean Ping, his ex-wife, and son are being officially investigated by Gabon’s Attorney General. Libreville prosecutor Steeve Essame Ndong mentioned a Sinohydro executive who, as part of a cooperation deal with prosecutors, admitted to and provided documentation of bribes paid to Frank Ping in a manner similar to the Brazilian Car Wash. Prosecutor Essame Ndong also summoned Jean Ping’s son, but the accused fled and is currently wanted by Interpol.

After being re-elected for a second time, Ali Bongo’s first diplomatic act was to visit the Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing on December 7, 2016, one year after the arrest of Sam Pa. The autocrat fell ill last October and, while convalescing, his brother-in-law Jean Ping laid claim to succeed him. Sinohydro clapped its hands.

GALERY | Contact in Angola

A Chinese model created among autocrats

On March 3, 2016, a team of French investigative journalists working for the online outlet Le DDM published details of Sam Pa’s confession from his trial in Beijing for the blood diamonds scandal in Zimbabwe.

According to the French account, Sam Pa confirmed that one of the main recipients of the millions in bribes channeled through the China International Fund (CIF) was the president of the African Union, Jean Ping, whose “good offices” were used by Sam Pa to expand the activities of the Chinese-Angolan oil consortium Sinopec-Sonangol not only in Africa, but also in Europe and Latin America.

“The scheme originated with the China International Fund, which is a kind of center for raw materials coming from Africa. This company was responsible for paying commissions to African politicians through shell companies”, revealed Le DDM’s report. Sam Pa mentioned Ping Ping and Consulting Limited of Gabon as one of the offshore companies to which Sinohydro had transferred a “tip” of more than four million euros for Pascaline Bongo and her son Frank Ping in April 2014.

The China International Fund is an intermediary company for Chinese capital, created at the end of 2003, nearly monopolizing the directing of funds from Eximbank to finance public works in African Union countries. (Its only “competition” was the Chinese government itself).

The CIF was one of dozens of offshore investment companies that Sam Pa set up in an intricate holding company housed in the Two Pacific Place building on Queensway Avenue in Hong Kong, for which the shady conglomerate is known in the world of finance as the “Queensway Group”. The Chinese magnate’s main partner in the CIF was Lo Fong Hung, a woman with high-level influence in the Communist Party and the Chinese government.

The success of Sam Pa’s expansionist strategy, based on his business in Africa through the CIF, allowed him to turn his voracity towards America and Europe. After consolidating Chinese and African offshore companies in Hong Kong, he settled in the heart of Wall Street, purchasing nothing less than the JP Morgan Bank building on one of the wealthiest corners in New York: 23rd St. However, his capitalist audacity would be the beginning of his end.

Upon entering the U.S. stock market, Sam Pa came under scrutiny from the State Department. It came to the attention of U.S. interdiction agencies that the Chinese magnate had a compulsive preference for doing business primarily with bloody African autocracies and dictatorships. The diamond business with the genocidal dictatorship of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe was evidence that the Chinese economists under Sam Pa “tended to repeat the experience of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile: only under a highly repressive regime is business growth such as that being promoted from China possible”, British analyst Tom Burgis of the Financial Times told Sol de Pando.

The Republic of Guinea, a neighbor of Sierra Leone, was another favorite autocracy of Sam Pa. On September 28, 2009, a massacre occurred at the Conakry stadium, with 150 dead and thousands injured by the military dictatorship that rules this Francophone country. Just two weeks later, on October 10, Sam Pa and his Angolan partners from Sonangol signed an agreement valued at seven billion dollars for Chinese investment in a variety of road, oil, aeronautic and hydroelectric projects, to be channeled through the CIF on Queensway.

According to journalist JR Mailer, Associate Researcher at the U.S. Defense Department’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Sam Pa, through the CIF and the Queensway Group, directed lines of Chinese credit to finance multimillion-dollar public works projects in Central African countries. In exchange, he took direct control over natural resources and raw materials (above all, petroleum, natural gas and minerals such as bauxite, coltan and diamonds).

The model is based on the following dynamic: African governments, looking to develop the transport, water or energy infrastructures promised in their electoral campaigns, offer their petroleum, gas or diamond reserves as collateral in order to obtain Chinese credit via CIF. These resources then pass into the hands of the shady conglomerate controlled by Sam Pa. Additionally, countries that receive financing from Eximbank, channeled through CIF, are obligated to hire Chinese construction companies and to buy Chinese machinery. “Beginning in Angola in 2003”, Mailer says in a dense study published in May 2015, a few months before Sam Pa’s imprisonment, “Queensway grew by developing extractive industries in a least nine African countries, including Guinea, Madagascar, Tanzania and Zimbabwe”.

The business and financial system created by Sam Pa is a devious combination of public resources and private investment, beginning with investments from Pa himself, through which state officials —including presidents— end up enriching themselves and their families.

“Focusing on the short-term objectives of senior government officials who control the natural resources of their countries, the consortium consummated business deals unfavorable to the general interest of their respective nations”, explains Mailer. He notes that the overwhelming flow of Chinese capital and African public resources concentrated on extractivism and the development of massive infrastructure projects and had no real impact on improving the living conditions of populations who continue to be among the poorest in the world. “The promises of high-profile infrastructure projects failed to materialize; allegations of corruption are widespread; respectable companies were excluded from the market, and the only beneficiaries over the years were Sam Pa’s business group and its African political partners”.

Evidence of payments made by Sinohydro to offshore consultancies registered in Queensway by Sam Pa on behalf of Jean Ping’s son. | Photo AfricTelegraph

The tentacles of corrupting neocolonialism

“Over the past decade, Pa has risen from obscurity to clinch deals across five continents worth tens of billions of dollars. He has helped to build from scratch a sprawling network of companies linked by common owners, directors and a registered address at 88 Queensway in Hong Kong. The group is in business with BP, Total and the commodity trader Glencore [whose subsidiary in Bolivia is controlled by the Venezuela Carlos Gill, -ed]. It boasts interests stretching from Indonesian gas and oil-refining in Dubai to luxury apartments in Singapore and a fleet of Airbus jets; it is active in North Korea and Russia. It comprises a web of private and offshore companies underpinning two main enterprises: China Sonangol, which is principally an oil company (although it also owns the former JPMorgan building opposite the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street) and China International Fund, an infrastructure and mining arm, whose flag flies above the entrance to Luanda’s golden skyscraper. Pa is not listed as a shareholder or director of any Queensway company but he does act as the network’s representative in meetings with presidents, sheikhs and tycoons. He has garnered power and wealth by making himself a middleman in China’s courtship of Africa – the development that has transformed the politics and prospects of the world’s poorest continent more dramatically than anything since the end of the cold war”.

Despite the failures of public works and the fall from grace of the Jean Ping and Sam Pa consortium, “the Queensway business model persists in Africa and other regions thanks to the lack of internal and international control structures,” says J.R. Mailer.

It’s a scheme of complete institutionalized corruption, where the abolition of fiscal control mechanisms and administrative regulation, as well as freedoms such as the collective right to information (without which a critical and observant public opinion is impossible), have become de facto corporate necessities for this new, predatory model masquerading as “socialist.” A model that also reigns in some Latin American countries within the neo-Stalinist orbit, such as Venezuela, Bolivia and Nicaragua.

LINKS RELACIONADOS

- SINOHYDRO SE DEVORA A ODEBRECHT

- Gobierno contrató a Sinohydro sabiendo que estafó y causó desastres en Ecuador

- Empresa china que busca ejecutar Cachuela Esperanza tiene problemas legales en Ecuador

- Trece muertos en derrumbe de Hidroléctrica ecuatoriana que construye la china Sinohydro

- Ministros de Bolivia eluden responsabilidad en tragedia del Chapecoense

- Hechos y dichos de Gabriela Zapata contradicen versión de su mentor

- Investigando a la Zapata reivindican Ley Marcelo Quiroga Santa Cruz

- QUINTANA, EL PADRINO DE LAMIA

- Emails demuestran que Micky Quiroga era dependiente y asalariado de Albacete

- El Gobierno de Bolivia encubre a narcotraficantes que manejan Lamia